I grew up in Provence, at the foot of the mountain of Lure, “Mont Parnasse gionien”; the poet liked to say that no one had better described this land than Shakespeare. It suited a little girl with green eyes and a fairy name.

On the plateau, she regularly visited two very old oaks that deserved her adoration: by swinging their branches heavily and waving their leaves, they made the wind, this great wind called the “scourge of Provence” but which she loved; These trees were Mistral makers, Titans. She dropped her bike and sat between the solid roots, in shorts, knees all scratched, around her neck throbbing a mysterious sapphire and silver pendant. And she watched the great branches shape the wind. And she listened to the voice, the hush, the deep rumor.

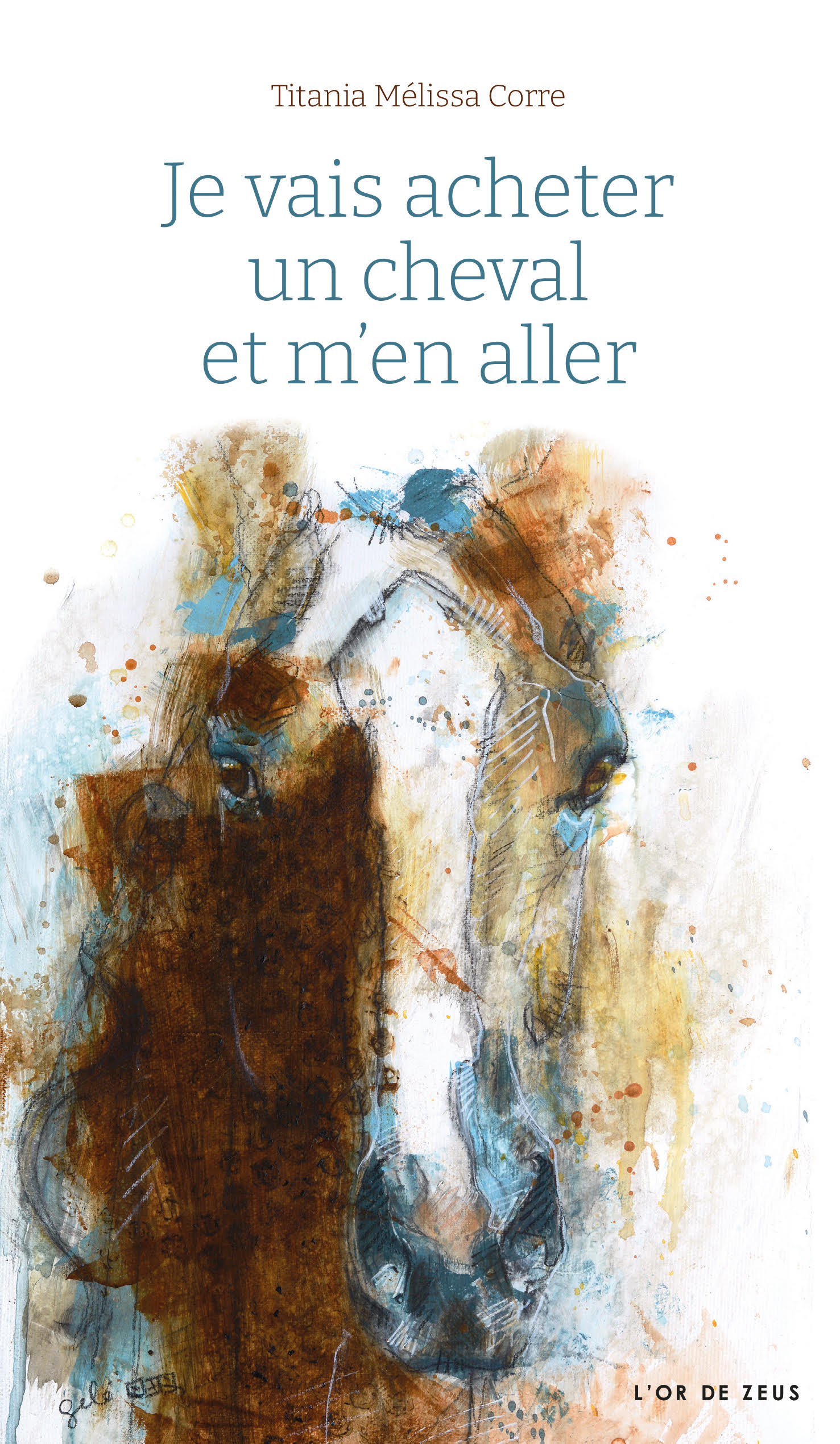

I do not know if someone smiled, if someone laughed, or if someone kindly explained that no, the trees do not make the wind my darling, that it is the wind on the contrary that shakes the trees. I only remember going from a fabulous world to a disenchanted world – without singing: there were no more wind makers. The bond that had naturally been woven between a little girl with a fairy name and the great oaks, between a fadette of the fields and the beasts, the woods, the springs had been brutally broken. Mab’s thread was cut. Everything had to be picked up and mended. The horses showed me how to do it. In a way, they are the ones who taught me to work.

And then I had to tell and write.